Notorious (1946)

Notorious has the best of everything: thrills, suspense and intrigue, an exotic setting, a “very strange love affair” between Hitchcock’s two favourite stars, a clever and complex plot of jealousy and deception, and some of Hitch’s giddiest direction.

Ingrid Bergman is at her most elegant and luminous as Alicia Huberman, daughter of a Nazi spy who is convicted and commits suicide at the beginning of the film. She meets and has a turbulent affair with suave, frighteningly handsome American agent, Devlin (Cary Grant), and travels to Rio with him to smoke out a group of desperate Nazi criminals there, headed by a former lover, Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains). In another recurring favourite theme of Hitch’s, Sebastian is clinging in a love-hate relationship with his distrusting mother, who suspects Alicia and is horrified when her son asks Alicia to marry him. She agrees, partly it seems to spite Devlin and her strange, tempestuous relationship with him. Their plan, it transpires, involves uranium ore hidden in bottles in the wine cellar. Devlin discovers this after Alicia steals Sebastian’s cellar key, leading to one of the most brilliant shots of the film: It is a party at Sebastian’s house. The camera drifts from the top of a staircase way above from where Bergman is talking to Rains. Slowly and smoothly it closes in, down, down, until Bergman nervously holds her hand behind her back, and eventually the cellar key she holds there fills the screen. It’s similar to an equally effective shot in Hitchcock’s earlier Young and Innocent, where he sweeps over the heads of people at a dance to the band behind and into the twitching eyes of a murderer.

Anyway, Sebastian realises his wife knows everything, and his mother convinces him to use a slow poison on Alicia. Hitch’s camera, which lingers on keys and wine bottles throughout the film until they take on a critical significance, closes in on tiny cups of poisoned black coffee. One wonderful shot is of Alicia in the background with an apparently gigantic cup in the foreground. Alicia grows sicker and weaker, until Devlin comes and ‘rescues’ her. The film ends with Devlin slowly and painfully escorting a drowsy Alicia past the Nazis and out of Sebastian’s house, leaving Sebastian to the mercy of the others, who also seem to twig just who it was Sebastian had married.

Marvellous stuff.

Dougal and the Blue Cat (1972)

This is the film where horridness hits the Magic Garden for the first time. For a small child, reared on the sweetness and innocence of The Magic Roundabout, to see the Garden devastated and covered in blue cacti, my heroes all chained up, Zebedee have his Magic Moustache stolen, and worst of all, Florence burst into tears was all quite shocking and unexpected. It’s like the Gary Larson cartoon: a picture of a sinking tanker and Puff the Magic Dragon dead in an oil-slick, over the caption “A tragedy occurs off the coast of a land called Honah-Lee”. This sort of thing just can’t happen. Dougal and the Blue Cat is a wholly wonderful film though, and if I want to make the (admittedly short) mental leap back to my childhood, it ranks up there with Doctor Who, Bagpuss and Bedknobs and Broomsticks.

With a big budget that allows for a bigger Garden with more hills, trees, houses etc, this is The Magic Roundabout on stronger drugs than usual. Amongst the colourful kids stuff and the hopelessly cute songs, our immensely talented (yet modest) yellow hero Dougal is hearing disturbing, other-worldly noises in the night. There’s the seductively sexy Blue Voice (Fenella Fielding, who could make a train announcement alluring) chanting, “Blue is beautiful, Blue is best! I’m Blue, I’m beautiful, I’m best!” from an empty treacle factory on top of a hill. All very sinister, and Dougal naturally reckons he’s going dotty and turns to the “painfully well-adjusted” Florence. But Florence and the others have meanwhile been taken in by new arrival Buxton, the spindly Blue Cat, who Dougal finds frankly rather dodgy from the outset. Of course Buxton and the Blue Voice reveal their true, wicked intentions to use their Blue Soldiers to take over the Garden (and then the Universe), and turn everything Blue! And so they do: “I’m so evil!” declares Buxton. With everyone locked up in huge chains in the Palace and things looking increasingly hopeless, it’s up to Dougal to dye himself blue, change his name to Blue Peter and rescue them (hoorah)! He does of course, and defeats the Blue Voice and Buxton in spectacular style. There’s even a trip to the Moon, complete with 2001 theme, to keep the sf fans happy.

The film is wonderfully inventive, and it constantly surprises me quite how dark and adult it gets in theme. At one point, Buxton throws Dougal in a torture chamber to prove whether he’s really Peter as he claims. The room’s full of sugar, and Dougal is forced to agonize between giving in to the sugar (which he loves as much as Dillon, er, enjoys sugar cubes) and giving himself away. It’s genuine psychological torture! He passes the test and is appointed Prime Minister, but life in the blissed-out Magic Garden was looking grim there for a while…

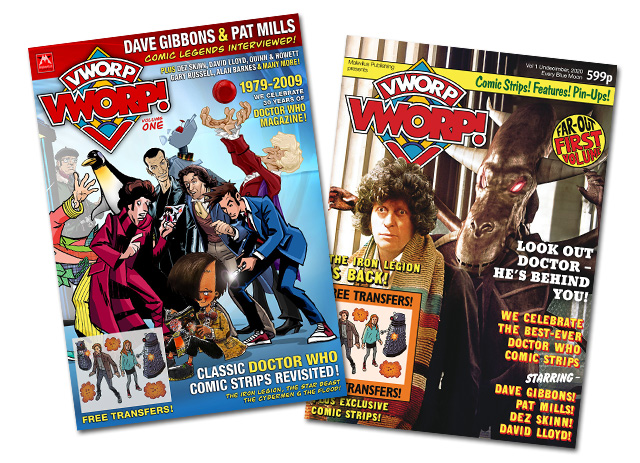

Way Out West (1937)

Way Out West is probably Laurel and Hardy’s greatest film. I adore this shambolic, perfectly matched couple, and this is sixty-five minutes of Stan and Ollie at their very funniest. The perfectly naive, wonderfully stupid but well-meaning Stanley, keeping the pompous, swaggering, frustrated Oliver just on the wrong side of sanity. The perfect comedy partnership.

The boys are on their way to the Wild West town of Brushwood Gulch to deliver a gold mine deed to their partner’s daughter. After failing to get a lift, Stan hits on the idea of showing a bit of leg to the next passing stagecoach, which literally screeches to a halt for them. Following a little impromptu soft-shoe shuffle, they meet the villainous bartender, Mickey Finn. James Findlayson plays a delightful pisstake of the nasties of the time: at his most dastardly he gives a chuckle, a gleeful rub of the hands, a little jump and then a look straight to camera as if for our congratulations at his villainy. Finn claims his brassy wife Lola (Sharon Lynne) is the woman they’re after. They hand over the deed, fooled (of course) by Lola’s display of crocodile tears on learning her so-called father is dead. “Is my poor daddy really dead?” she asks, overcome. “I hope so,” Stan says. “They buried him!” However, they discover the real heiress Mary (Rosina Lawrence) working as Finn’s scullery maid, and rush back upstairs for the funniest part of the film.

Stan and Ollie jump around Finn’s room, throwing the deed from one to the other in an increasingly desperate and frenetic attempt to stop it getting into the hands of Finn and Lola. Laurel darts into the bedroom with it, pursued by Lola, who locks them both in. Even when alone with this terrifyingly sexual woman, Laurel holds onto the deed then stuffs it down his shirt triumphantly, where he thinks she can’t get it. Lola dives in after it and reduces ticklish Stan to wild hysterical laughter, legs flailing about everywhere. He’s still at it when she leaves the room with the deed! One of Stan Laurel’s finest hours.

The climax has Stan and Ollie break into the saloon. Ollie somehow gets his head stuck through the flap of a trapdoor and Stan tries to pull Ollie’s body through, stretching Ollie’s neck about four feet before it springs back like elastic. Eventually of course, Mary gets her deed, Finn gets his comeuppance, tied to a chandelier, so everything’s all right… Phew.

There’s some great recurring sight gags, such as the scenes that top and tail the film. At the beginning, Stan and Ollie wade across a river and -whoosh! – Ollie suddenly disappears down a pothole. It happens again at the end, but of course in the other direction! Similarly, Stan’s ability to light his thumb like a match gets Ollie in a panic when finally he manages it himself.

Laurel and Hardy are the ultimate feel-gooders as far as I’m concerned. Complex Way Out West ain’t, but lawks it’s funny and I have simple tastes!

Ice Cold in Alex (1958)

One of my top five. Ice Cold in Alex is a war film, and yet it doesn’t deserve to be pigeonholed as such (I’m not much of a fan of straight war films). It’s a psychological story of endurance, friendship, teamwork, lots of sweat and a hint of romance, with the war film trappings of German spies, tanks, bombing and a constant threat of danger. And it’s the story of a beer advert.

It tells the (slightly true) story of five people and an ambulance called Katie, on a hazardous drive from Tobruk to Alexandria during World War II. In between: the constantly advancing front of Nazis and “The Greater Enemy”, six hundred miles of desert, two hundred miles of which is the Qattara Depression, “liquid underneath with a sort of dried crust on top, rather like a mouldy rice pudding”. And Katie weighs over two tons, remember…

John Mills is utterly convincing as the hard, determined but emotionally and physically exhausted Captain Anson, overworked to the extent that even when he was captured and on the run for two days without water before the film starts, he’s still allowed no break. He knows a little bar in Alexandria where he promises to buy the others a glass of the best beer in North Africa (ice cold, of course). “I’m gonna get Katie to Alex, you understand?” he says. “It’s a personal thing.” Along the way, there’s a little romance with rather drippy nurse, Diana Murdock (Sylvia Syms), presumably only because she’s the only totty around, as she’s an utterly useless individual otherwise. It could have got quite saucy if the censors hadn’t balked at such fleshy abandon. Hysterically scared Sister Denise Norton (Diane Clare), another nurse stranded in Tobruk after its evacuation, comes along for the ride but soon gets fatally shot by a pursuing German tank, much to the consternation of solid and reliable mechanic Sergeant Major Tom Pugh (Harry Andrews). They meet suspicious Captain van der Poel (Anthony Quayle), who claims to be an Afrikaner but has a dodgy accent, doesn’t know how to light fires like any soldier should, has a radio transmitter, and gets up Anson and Pugh’s noses with his brash and overbearing personality. Not surprisingly, along the journey they reveal van der Poel to be a German spy, although they’ve grown so fond of him by the time they have to turn him in at Alex that they save his life by lying for him when he’s arrested.

The film is full of nail-biting set pieces. Early on there’s the ambulance’s painstaking journey across a huge live minefield, Anson and van der Poel advancing at a snail’s pace in front as they check the tracks for mines. Later, one of Katie’s springs goes and Pugh jacks her up and piles rocks under her to support her. With van der Poel underneath, Pugh releases the jack and the rocks start to crumble with the weight. You can almost feel the pain on Anthony Quayle’s face as he supports a ton on his back while Pugh desperately pumps up the jack. Then there’s the scene where van der Poel is trapped in quicksand-like mud, sinking slowly and desperately trying to push his incriminating radio transmitter under, unable to keep hold of the rope, slippery with mud, that Anson throws him.

The best scene of the lot though, is near the end. Confronted with a steep slope of sand that seems impassable, Anson, van der Poel and Pugh take it in turns to wind the ambulance’s starting handle, which agonisingly inches it towards the summit. When, almost at the top, Anson asks Diana to hold the handle while he gets his shirt, you know the ambulance is going to end up right at the bottom again.

It’s a wonderful film, shot through with tension and frustration. Lensed in Libya by director J Lee Thompson, it has grittily authentic feel, the aridity and heat almost palpable. Finally Anson gets his glass of Carlsberg and devours it like Cary Grant devours Ingrid Bergman instead of a plate of chicken in Notorious. “Worth waiting for,” the Captain says.

40 things I hated…

40 things I hated… D I McMillan: awful awful awful, like a bumbling comedy policeman from an episode of Terry and June. Or CBeebies. “It’s definitely her, come on! Jackson, follow that bus!” Perfectly reasonable lines, but from the mouth of Adam James somehow… shit. And later he says “You do not have to say anything, et cetera et cetera” which proves he’s a rubbish copper too.

D I McMillan: awful awful awful, like a bumbling comedy policeman from an episode of Terry and June. Or CBeebies. “It’s definitely her, come on! Jackson, follow that bus!” Perfectly reasonable lines, but from the mouth of Adam James somehow… shit. And later he says “You do not have to say anything, et cetera et cetera” which proves he’s a rubbish copper too. “Angela. Angela Whitaker.” Is there a section in Spotlight containing Victoria Alcocks, Jacqueline Kings, Lesley Sharps, Camille Coduris, Helen Griffins, etc etc? Dour women of a certain age and a certain look, capable of a certain expression, with overweight husbands called Mike.

“Angela. Angela Whitaker.” Is there a section in Spotlight containing Victoria Alcocks, Jacqueline Kings, Lesley Sharps, Camille Coduris, Helen Griffins, etc etc? Dour women of a certain age and a certain look, capable of a certain expression, with overweight husbands called Mike. And Captain Magambo, words cannot express the violent feelings I experience every time I see your face or hear your strangely monotone voice. And I don’t like your shoes.

And Captain Magambo, words cannot express the violent feelings I experience every time I see your face or hear your strangely monotone voice. And I don’t like your shoes. How irritating and out-of-character does Christina get when she realises she’s got “dead people” in her hair? Argh!

How irritating and out-of-character does Christina get when she realises she’s got “dead people” in her hair? Argh! 40 things I loved…

40 things I loved… Lou. I like you, Lou, shame your missus is bonkers.

Lou. I like you, Lou, shame your missus is bonkers. There’s a very nice shot of Christina’s bottom. Thank you Russell, for this concession to your heterosexual viewers.

There’s a very nice shot of Christina’s bottom. Thank you Russell, for this concession to your heterosexual viewers.