This article was published in its original form in Circus #1. As well as revising the arse out of it, I’ve taken the opportunity to add a number of fancy sound clips. I hope you enjoy it!

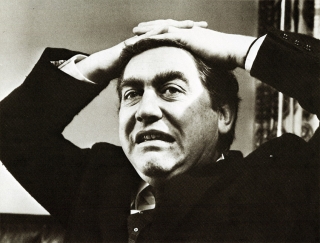

Interviewer John Freeman, in his famous 1960 Face to Face interrogation, wasn’t the first to assume a certain comic genius’s true name was Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock. By then the real Anthony John, with all his flaws and eccentricities, had become inextricably ingrained in his fictional persona, as much as he tried to distance himself from it. He told Freeman: “It isn’t a character I play, that I put on and off like a coat. It is greatly a part of me and a part of everybody else that I see.”

Before the first radio Hancock’s Half Hour, on November 2nd 1954, Tony Hancock had become quite a regular on TV and radio, most notably as the tutor of ventriloquist’s dummy Archie Andrews in the last 26 episodes of Educating Archie, a radio comedy by Eric Sykes and Sid Colin. He was also well known from his stage appearances, in successful variety shows such as London Laughs and Talk of the Town, and in panto (which he despised). Inspired initially by the likes of Max Miller and Sid Field, he slowly developed his own distinctive style which, coupled with perfect timing and a degree of audience control and manipulation that was important to live performers, guaranteed that his audience laughed in all the right places. But, no matter how perfect the medium was for him, Hancock disliked working on the stage. He was terrified of it and was often physically sick before going on.

Ray Galton and Alan Simpson writing partnership had been forged as teenagers, when they had found themselves in the same TB sanatorium for several years. “We had a lot of time on our hands, making handbags, listening to the radio,” and so they began writing comedy for hospital radio. Their work progressed until, in 1951, their material was used by Hancock for the first time. They were perfect for each other, and became his regular writers. In 1954 Hancock, Galton and Simpson were given a radio show to themselves, and on November 2nd Wally Stott kicked off ‘The First Night Party’ with the dopiest theme music ever written.

Over the course of three years and countless sketches and shows the rich Hancock ‘character’ was developing. Of this fictional Hancock, Ray Galton said: “It was really seedy grandeur. Everyone could see he was pretentious and seedy, except himself of course, and that was really the basis of his character.” Many of Hancock’s own traits were brought into the character, such as his own lack of success with women, a rather mean streak, and his desire to be an intellectual and philosopher in ‘Bertie’ Russell mould, constantly striving for fundamental truths. It was because of Hancock’s honesty about himself that he allowed Galton and Simpson to derive humour from his true character, and the three of them were fortunate in that they shared similar attitudes and senses of humour. The character was very complex and, for all his irritating quirks, still utterly endearing and real.

Radio comedian and ‘resting’ thespian Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock (the Second) believes himself to be basically perfect in most respects, but discovers the hard way that he falls far short in all of them. In his own eyes, he is a good-looking devil (“What I don’t know about women could be written on a pinhead with pneumatic drill”), vastly erudite (“Ah, that’s the Great Bear up there… It’s mythology; and the Mythologians were the greatest navigators in the world. Do you realise they were in America long before Columbus? And they only had little ships, too!”)… in fact far too good to be living with simpletons in East Cheam, the tatty and disreputable end of the borough, in a ramshackle old semi-detached (“Even the foundations are shifting… You look in the deeds. 23 Railway Cuttings, Cheam, yeah? Forty years ago it was number 11!”).

To quote from Roger Wilmut’s excellent book Tony Hancock – ‘Artiste’, our hero is “a failed Shakespearean actor with pretensions to a knighthood and no bookings; age late 30s but claims to be younger; success with women nil; a pretentious, gullible, bombastic, occasionally kindly, superstitious, avaricious, petulant, over-imaginative, semi-educated, gourmandising, incompetent, cunning, obstinate, self-opinionated, impolite, pompous, lecherous, lonely and likeable fall-guy.”

‘Agricultural ‘Ancock’ showcases some of Hancock’s rather bizarre ideas, this time about life in the country, that big town without any buildings in. “I still haven’t forgotten that trip into the country last year when we came across those ducks in the pond,” recalls Hancock’s secretary, Miss Pugh. “What was that brilliant remark you made? ‘They must have whopping long legs to walk across that!’” To keep the rent down on Number 23, Hancock needs to prove he’s an agricultural labourer by buying a farm:

HANCOCK: “Anybody can make a go of farming. A little planning, that’s all. Rotate your crops. Rotate ‘em. Get ‘em going round, that’s the secret. I shall start off with, let’s see, I shall plant two fields of pigs and a couple of acres of chickens.

MISS PUGH: “You’re going to plant some chickens?”

HANCOCK: “Certainly. How do you expect them to grow? Get ‘em buried up to their necks, wait for a bit of rain, we should have a nice crop of eggs… They’re exactly the same as rabbits. I saw two rabbits dig a hole in the ground, disappear, and when they came up there was hundreds of ‘em. If rabbits can do it, so can pigs and chickens.”Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Things don’t go according to plan of course, as Hancock unwittingly buys, and starts farming, the Lords Cricket Ground from his ‘friend’ Sidney James.

Unfortunately for Hancock, Galton and Simpson populated his life with various foils and pestilences. Chief among them was Sid James, the small-time crook and archetypal loveable rogue. Sid constantly preys on Hancock’s utter gullibility, with schemes that usually leave the latter out of pocket. In ‘A House on the Cliff’, Sid convinces Hancock he needs to build three houses, one at the top of a cliff, one on the beach below – with two escalators to take them in-between – and another house two miles inland, connected by a railway (the one at the bottom of the cliff to live in during the day; the one at the top for when the tide comes in at 8pm; the escalators – one up, one down – to carry him and his furniture; the one inland to live in if the weather gets rough and the cliff collapses, with access by train courtesy of the Sidney James Engineering Company – “He’s dead right,” says Hancock, “I’m surrounded by idiots!”). In ‘The Insurance Policy’, so he can “lay about with impunity”, Hancock takes out cover with the Sidney James Friendly Accidents Society, from being struck by lightning, run over by steam-rollers, run down by stampeding cattle, falling down lift shafts, assassination, sunstroke, earthquakes, frost and snakebites (with an income of £10 a week, and taking into account he used to drink, smoke and can’t afford to feed himself any more, Hancock’s premium turns out to be £13 14s 6d. Result: misery). In ‘The Income Tax Demand’, chartered accountant Sid helpfully fabricates a series of expense sheets and ‘mystery investments’ that increase Hancock’s tax bill from £14 12s 3d to over £170 000 (“I’ve got another set of books here proving I never saw this bloke before in my life!” says Sid in court, when things start getting serious). It was probably Sidney Balmoral James who sold Laurel and Hardy the Brooklyn Bridge.

HANCOCK: “The man’s a scurrilous scalliwag.”

BILL: “Well, you said it.”

HANCOCK: “Only just.”

(‘The New Car’)Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Sid James was as impeccable as ever in Hancock’s Half Hour.

And then there was Australian vagabond, Bill Kerr, he of the blink-and-miss-it appearance in The Dambusters (as Hancock delightedly points out) and later, Doctor Who‘s ‘The Enemy of the World’. Rather like Baldrick in The Black Adder, Bill’s character began life as a fast-talking intelligent type in the first two series, a voice of sanity between Sid’s schemes and Hancock’s gullibility. The problem was that that voice was already being supplied by the current female character, so by the third series Bill had evolved into the endearing idiot.

William Montbeaurency Beaumont “Billabong” Kerr, like Hancock, is a lazy unemployed actor (most of the time – these things changed weekly to suit the storyline). Born in Wagga Wagga, he shares Number 23 with “Tub” Hancock, who’s regretted it ever since. The character has a delightful air of childlike innocence and although he rarely contributes much to the storyline, usually has some of the most hilarious, nonsensical lines and exchanges:

HANCOCK: “If you’re going to learn how to read and write you’ve got to start right at the very beginning. There is no short cut to literacy… ”

BILL: “… Where’s that?”

HANCOCK: “Where’s what?”

BILL: “Literacy?”

HANCOCK: “What are you talking about?”

BILL: “You said there was no short cut to it.”

HANCOCK: “That’s right.”

BILL: “Well, how did you get there then?”

HANCOCK: “William, literacy is not a place.”

BILL: “What is it then?”

HANCOCK: “It’s a state of being.”

BILL: “Being what?”

HANCOCK: “Being literate.”

BILL: “Ohhh. My dog had two literates once…”

HANCOCK: “Your dog did not have literates. Your dog had litters. L-I-T-E-R-S.”

(‘Hancock’s School’)Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

The role of ‘sensible female’ went initially to Moira Lister (whose film comedy, including Norman Wisdom’s film debut Trouble in Store, proved that she should be seen as well as heard!), then in April 1955 to Andrée Melly (The Belles of St Trinian’s, The Brides of Dracula), playing a French girl who suspiciously loses her accent between series. Both were described as Hancock’s ‘girlfriends’, a relationship which sounded more and more unconvincing as Hancock’s character developed, and as a result they became rather a fifth wheel to the serious stuff of making people laugh. So out went Andrée and in came the wonderful Hattie Jacques as the massively proportioned Miss Grizelda ‘Grizzly’ Pugh, the ‘New Secretary’ of November 1956. Only then did the team truly hit perfection.

After having trouble with his paperwork, Hancock puts an ad in the paper: “Secretary wanted. Blond, 19, 37-22-36½, or nearest offer… well that ought to attract the wrong sort of girl.” In walks the large-boned Miss Pugh, who apparently is constantly being mistaken for a famous Beauty Queen (Hancock: “What a mistake!”). Following countless jokes about her size (Hancock asks what happened to the promised 36-23-35½; “It’s all here,” explains Grizzly proudly. “I didn’t mean your leg measurements, dear!”) and lack of office space, Hancock hires her after she explains the purpose of her umbrella, with its weighted end and rust-coloured stains. Further complications arise when Sid grows infatuated with this mysterious Eastern princess, brought about initially by his discovery that the fascinating Miss Pugh signs Hancock’s cheques. A certain friction occurs in ‘Cyrano de Hancock’, when Hancock mistakenly proposes to an over-eager Miss Pugh. Naturally, Hancock escapes Sid’s big knife when he accidentally marries the registrar, played by Kenneth Williams.

KEN / ‘SNIDE’: “I listen to your radio show every week.”

HANCOCK: “Oh, do you like it?”

SNIDE: “No, I think it’s rotten. All except that bloke with the funny voice. He’s a scream, isn’t he? Ooh, he has me in stitches. You know, there are actually people like that.”

HANCOCK: “Get away!”

SNIDE: “No there are, honest. I met some. You wanna hang on to him. Only thing in the programme, he has me on the floor…”

(‘The Emigrant’)Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

A vastly erudite man, Kenneth Williams was undoubtedly a comedy great. Just a few words after affecting his trademark thin nasal voice, whether they be “Good eve’nin’” or “Stop messin’ about” or “Don’t be rotten”, was enough to reduce an audience to hysterics. It was a great shame he clung onto the Carry On films throughout their run; good as he was in them, his insecurity made him shy away from diversifying into more challenging roles on film and stage. Indeed, it seems a further ambiguity to his character that, as revealed in the The Kenneth Williams Diaries, he found all of these comedy parts very much beneath him.

But Hancock’s Half Hour was near the beginning of his career and fame found him quickly. He played a range of characters, adopting the voice of gruff old men, suave sophisticates, irritating officials, inept doctors, judges and the like, but after the third series he became most famous for the seemingly omnipresent whining idiot christened off-air as ‘Snide’. He would usually appear towards the end of episodes, and would invariably get more laughs than Hancock. (That was to be the Ken’s downfall: he left soon after Hancock had Snide removed before the fifth radio series in 1958, criticising Williams’ “cardboard caricatures”, and he only appeared in a handful of the earlier TV shows.)

‘The Diary’ closes with one of Hancock’s Half Hour‘s most famous sequences, ‘The Test Pilot’, in which our hero imagines himself as Wing Commander Hancock: RAF stiff upper lip, pride of England and massively moustached (Bill: “The best thing to do is tie it around the back of your neck, it’ll cut down wind resistance”). Taking a revolutionary, wingless, vertical take-off plane out through the fanlight, Hancock is informed that the mechanic has gone missing. Until, that is, he hears a strange tapping on the cockpit and slides it open. It’s Kenneth Williams’ Snide, who’d been working on the tail, singing to himself, when: “Whooosh! I was up ‘ere.” Kenny accidentally discovers the ejector switch and they both end up clinging to the tail:

SNIDE: “Isn’t life funny? In the papers this morning, the stars said it was my lucky day.”

HANCOCK: “If we keep going up at this rate, you’ll be able to tell them they’re wrong!”

SNIDE: “… Oooh, I’m scared. Oooh!”

HANCOCK: “Don’t panic, man. This is the RAF. Where’s that stiff upper lip?”

SNIDE: “Just above this loose flabby chin.”Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

If Anthony Hancock had one true friend in the series, it was the nameless character played by co-writer Alan Simpson in the earlier episodes. A bystander, he was the rapt audience to Hancock’s long-winded tall stories, and occasionally had delusions of stardom by ad-libbing more than the odd “Yes”, “Dear oh dear” or “Did you really?” The stories were little more than padding, and were dropped by the third series. Here’s a good example, from ‘A House on the Cliff’ (the italicized bits are Simpson):

I come from a long line of builders, me, you know. [Do you?] My great grandfather helped to build the Tower Bridge. [No?] Yes, he was the bloke who sawed it in half. [Was he?] … Anyway, me biggest job, that was the one I was going to tell you about, undoubtedly was the Forth Bridge. [Ah, yes] It was the Forth Bridge. I remember distinctly because the other three fell in. [Did they?] Yes. Anyway, I was in charge. I decided we’d start building from both sides and meet in the middle … We were going along like a house [On fire?] On fire. You should’ve put that in. We’d build the first 27 yards in three seconds. [No?] Well, we had to. There was a train behind us! Well, we was doing very well right up until the fog sprang up. [Ooh dear] Well, I dunno how it happened: the long and the short of it was, we passed each other. Well, I felt a right toby jug, I’m telling you. [Well, you would do] There was the other half of the bridge twenty yards past me and six feet on one side. Well, I blamed it on the crane driver. ‘Course the bloke who was the lifting the big girders about; ‘It’s your fault,’ I said. I was annoyed. [Well, naturally] Puce, I was. [Yes] The whole face was red with anger. [You said 'puce'] Well, I did. I got the right to change my mind, haven’t I? [Yes] Thank you very much. [Carry on] Just keep chipping in, don’t try and dominate. Well, as I said me whole face was red with anger. I clenched me fists till the muscles on me arms stood out like marbles. I went over to him, I shook me fist. ‘It’s your fault’, I said. ‘You weren’t looking where you were going’, I said. ‘Undo all that lot’, I said, ‘and go back and start again’, I said. It was me speaking. Well, I don’t know whether it was the authority in me voice, or the sense of shame he must have felt, but he did it without a murmur. I should have said, he done it without a murmur, I’m sorry. [It doesn't matter] Grammatical mistake, we can all go wrong. He could see I meant it. He started his crane up and got going, ‘cos he was eager to rectify his mistake, see? [Yes, of course] Anyway, I’ll never forget it, never forget it, just as if was today. Swinging this huge crane around like a toy, dead keen. And do you know, he had a sort of sheepish, apologetic smile on his face as… just as I walked away … having won me point… being the foreman – do you know what he did? [What?] He dropped a ten tonne girder on me head…

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Galton and Simpson often gave full rein to their imaginations in earlier episodes, resulting in many far-fetched storylines. These often took the form of fantasy or dream sequences which involved Hancock becoming Prime Minister, Father Christmas or, as in the aforementioned ‘The Diary’, an eminent surgeon, lion trainer and test pilot. In the wonderful ‘The Emigrant’, Hancock’s desperate attempts to enter Australia, Canada, South Africa, India or even Baffin Land culminate in a journey on a plane ‘piloted’ by Snide. Inevitably it crashes, and Hancock finds himself at the pearly gates. When Hancock announces himself, an angel suggests, “Have you tried the other place?”

Galton and Simpson often gave full rein to their imaginations in earlier episodes, resulting in many far-fetched storylines. These often took the form of fantasy or dream sequences which involved Hancock becoming Prime Minister, Father Christmas or, as in the aforementioned ‘The Diary’, an eminent surgeon, lion trainer and test pilot. In the wonderful ‘The Emigrant’, Hancock’s desperate attempts to enter Australia, Canada, South Africa, India or even Baffin Land culminate in a journey on a plane ‘piloted’ by Snide. Inevitably it crashes, and Hancock finds himself at the pearly gates. When Hancock announces himself, an angel suggests, “Have you tried the other place?”

The writers possessed a great skill for vividly conjuring up the most implausible scenes and situations through dialogue and the economic use of sound effects. They also took great risks with their use of silence – usually considered ‘dear air’ on the radio - as in the well-known ‘Sunday Afternoon at Home’, which conveyed crushing boredom with its long, and somehow hilarious, stretches without dialogue. Similarly, ‘Sid James’s Dad’ features about a minute of just clattering metal as Sid, in an act of good will and generosity, empties his pockets and returns everything he stole from Hancock during his last visit.

However hilarious the results of their earlier flights of fancy were, Galton and Simpson seemed to realise over the course of the series that it was the humdrum of everyday life that inspired the funniest material. Such simple scenarios include trying to get to sleep, paying a tax bill, buying a car or a television, going on a picnic or a hospital visit, or getting home from the cinema. Full of accurate observation, these scripts reveal absurdity in the mundane.

It would be untrue to say that every one of the scripts is a masterpiece but Galton and Simpson did maintain a consistent quality throughout the 103 radio Half Hours, particularly from the fourth series onwards, by which time they had truly nailed the radio medium and Hancock’s character. Each story has the seemingly effortless feeling of having been improvised by the cast as they went along, and the scripts seem almost naturalistic (in a comedy framework) because of this.

By the sixth radio series in 1959, the television version of Hancock’s Half Hour was seriously overshadowing its counterpart. With Tony Hancock the highest ranking TV star at that time, he decided to move on from radio and only undertook the sixth series with reluctance (also, since it had to be hastily written, he was concerned that it might not be up to scratch). On 29th December 1959, two days before the beginning of a new decade, the final radio episode, ‘The Impersonator’, was transmitted.

Hancock himself remains something of an enigma; his talent is plain for everyone to see and it is difficult to understand why he was forever dissatisfied with it. He constantly strived for some elusive ‘secret of comedy’ that would somehow enlighten mankind. As he said himself to John Freeman: “The only happiness I could achieve would be to perfect the talent that I have, whatever it may be, however small it may be, that is the whole purpose it of it and that is the whole purpose of what I do.” This would seem to have been unattainable as Hancock discovered when he rid himself of the team that had contributed so much to the success of the radio and television series. He went his own way and everything went downhill from there.

That the radio Hancock’s Half Hours worked was down to the show’s perfect combination of actors and writers, particularly during its heyday with Hattie Jacques. Although Tony Hancock had top billing, it’s the interplay between the whole array of contrasting and likeable characters that made it so special. Like so many comedy shows from the time, it was a collective effort. The humour was not complicated, but then it didn’t have to be. Tony, Sid, Ray, Alan and the rest of the team made people laugh - and it’s a rare achievement that today, half a century later, they still are.

You know those beastly fellows at

You know those beastly fellows at