To accompany my interview with Sam Youd, this is an article I wrote in 1999 for Circus 8 on Sam’s best known pen-name, John Christopher, under which he wrote such enduring classics as the Tripods and Sword of the Spirits trilogies and The Death of Grass.

In a review in the Independent newspaper of Brian Aldiss’ autobiography, The Twinkling of an Eye, John Christopher was said to be one of the five ‘most important British science-fiction writers’. Aldiss himself has often spoken of his admiration for John Christopher, describing him in Billion Year Spree as ‘an intelligent and witty man, marvellously equipped as a writer’. One rarely comes across this kind of recognition, which is a great shame as John Christopher, real name Sam Youd, fully deserves it for his important contribution to British science fiction over the last fifty years.

Christopher Samuel Youd was born in 1922 in Knowsley, Lancashire (‘the rural hinterland of Liverpool,’ as he once described it), but left for Hampshire at the age of ten, ‘a manoeuvre which he regards as in a sense equivalent to Dickens’s banishment to the blacking factory,’ where he attended Winchester’s Peter Symonds School. He became interested in science fiction at around the same time, particularly the American magazine stories that influenced the likes of John Wyndham, Arthur C Clarke and Kingsley Amis; he began his own sf fanzine, The Fantast, when he was seventeen. His first professionally published short story, ‘For Love of Country’, appeared in Lilliput in late 1939 (‘It was about an Anglophile German bomber pilot who tried to drop his stick in open country but hit the cleverly camouflaged factory my train passed every morning on my way to my job as a clerk in the County Medical Office at Winchester’). He served in the Royal Corps of Signals during World War II, and seriously turned his hand to writing after he was demobilised in 1946 and working in general publishing, then as assistant editor of a technical journal. Along with a number of young writers who could claim their careers had been interrupted by the war, he was given an Atlantic Award by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1946 (married by then, he was awarded the full £300, but had to promise not to do any non-writing work for a year). His first sf short story and his debut novel both appeared in 1949.

The story was the ‘Christmas Roses’ (published as ‘Christmas Tree’ in Astounding, February 1949, and still being reprinted as recently as 1979). It’s the melancholy story of Major Joe Davies, navigator on the Arkland. Anyone serving aboard a spacecraft is given a medical after landing, to assess the ‘cumulative stress’ on their heart caused by take-off and landing. Some last up to ten years from their first warning until they’re judged incapable of withstanding the strain – then, wherever they are, they’re stuck for the rest of their lives, ‘the exile, the outlaw who left it too late to get back’. Davies arranges to take a Christmas tree up to an old man, Hans, who has been stuck on Luna City, ‘a couple of blocks long, a block wide’, for forty years. While buying the tree, he is struck by the beauty of the countryside around Washington and decides he’ll retire there when he returns, to grow fir trees and Christmas roses. On arriving on the Moon, Davies discovers Hans died the night before; then, worse still, he fails his medical. At the end of the story, Davies mournfully watches Earth and the stars from the lunar surface – ‘I keep thinking I can smell roses.’

‘Christmas Roses’ is an assured and confident story dealing with timeless themes that still has the power to move – in fact, the only way in which time has been unkind is in the story’s talk of lichen and lunar insects that consume the dead. Youd would return to the premise of imprisonment in a lunar station in his children’s novel The Lotus Cavestwenty years later.

The Winter Swan (1949) is a mainstream novel, but told in a manner not unfamilar to science fiction readers (of Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow, for example), A common judgement of first novels is that they were often autobiographical, but he was determined not to qualify in that respect and instead told the story of an old woman named Rosemary Hallam. He then further reversed the norm by beginning the novel at her graveside in 1949, then telling her life story in reverse. Part of the interest of the novel arises from seeing the effect before the cause. Despite this striking originality, the novel was not a critical or commercial success (the Times Literary Supplement grudgingly admitted it was ‘not uninteresting’).

The Winter Swan (1949) is a mainstream novel, but told in a manner not unfamilar to science fiction readers (of Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow, for example), A common judgement of first novels is that they were often autobiographical, but he was determined not to qualify in that respect and instead told the story of an old woman named Rosemary Hallam. He then further reversed the norm by beginning the novel at her graveside in 1949, then telling her life story in reverse. Part of the interest of the novel arises from seeing the effect before the cause. Despite this striking originality, the novel was not a critical or commercial success (the Times Literary Supplement grudgingly admitted it was ‘not uninteresting’).

Unperturbed, Sam Youd continued to write mainstream novels in his spare time to supplement his poor income. Now with a family to support, he wrote, in a single draft, realistic and socially-aware novels, ‘penetrating the hidden motives of human behaviour’ (as the blurb of Holly Ash (1955) puts it). There was still the occasional fantasy element – the suggestion that Piers Merchant, the main character of Babel Itself (1951), might actually be the Devil, for instance – but Youd’s interest in sf was finding an outlet in the short stories he was writing at the same time, for sale to such magazines as Galaxy, Science Fantasy and, most notably, New Worlds. Most of them were set in the twenty-second century, where countries have been replaced by mega-corporations called ‘Managerials’; the thought being that entities governed by politics will slowly destroy civilisation, but commercial interests will perpetuate it. Individuality and creativity are no longer treasured. It’s all worryingly prescient. Many of these stories feature the exploits of Max Larkin, a director in one of these corporations, and all but one were written under Sam’s best-known pseudonym, John Christopher. A later novel, The Year of the Comet (1955), is set a century earlier and explains how this situation came about, wrapped up in a clever but wordy tale of Managerial plots and counter-plots.

The Managerial stories are collected in The Twenty-Second Century (1954) and although they are interesting, it’s in the other stories that pointers to future John Christopher themes are clearest.

The end of the world as we know it

In ‘Blemish’ (1953), enlightened aliens threaten to wipe out a supposedly advanced future Earth unless mankind relearns the value of family life from a small rural village it labels the ‘nut house’. We show our true colours in ‘Monster’ (1950), when a peace-loving creature on a mission to save its race is shot as it tries to make contact at Loch Ness. In ‘Begin Again’ (1954), radiation sickness from a nuclear war has wiped us out, and the last man on Earth meets the last woman against a grim backdrop of devastation – I’ll leave you to guess their names. In ‘The New Wine’ (1954), telepathy is induced into every unborn child, who go on to see a side to human nature so ugly they either die, commit suicide or chose celibacy. In short, the world ends, the thin veneer of civilisation removed.

The third John Christopher novel, The Death of Grass (1956), deals with this theme with visceral power. Although The Year of the Comet mentioned how the Managerial system had its roots in a similar disaster two centuries earlier (‘They got the lot – atom bombs, hydrogen bombs, breakdown, disease, famine’), here the author gives us the kind of description of the collapse of civilisation he would become famous for.

A mutant virus that kills all types of grass appears in China, and slowly works its way towards Britain, leaving starvation in its wake as grain crops wither and animals starve to death. Our scientists are smugly confident they can combat it, but the Chung Li virus, as it becomes known, develops new phases with unexpected speed and finally reaches us. John Custance, an architect, is warned by old Army friend Roger Buckley that their families should flee from London to John’s brother David’s farm in the Lake District. Friends in high places have informed him that the British government are planning the extreme step of bombing major cities before the now inevitable suffering and anarchy overwhelms them. Meeting the deceptively courteous gunsmith Henry Pirrie and his wife on the way, they begin a dangerous race for survival across a rapidly degenerating country.

The national politics are cleverly and convincingly depicted, but the politics within the small group are more interesting. Roger, initially a major player in the book, quickly falls into the shadow of John as John’s uneasy relationship with Pirrie develops. Although John instinctively distrusts Pirrie, never more so than after Pirrie claims the right to execute his own wife, Millicent, for her repeatedly unfaithful behaviour, they soon learn to rely on one another. Pirrie needs John natural leadership skills, and John’s disgust at Pirrie’s brutal methods turns to a kind of admiration. John, through a series of encounters with violent bands, adopts Pirrie’s survivalist tactics, killing in cold blood whoever gets in his way, dispatching the weak who, by his and Pirrie’s rationale, with die soon anyway.

The national politics are cleverly and convincingly depicted, but the politics within the small group are more interesting. Roger, initially a major player in the book, quickly falls into the shadow of John as John’s uneasy relationship with Pirrie develops. Although John instinctively distrusts Pirrie, never more so than after Pirrie claims the right to execute his own wife, Millicent, for her repeatedly unfaithful behaviour, they soon learn to rely on one another. Pirrie needs John natural leadership skills, and John’s disgust at Pirrie’s brutal methods turns to a kind of admiration. John, through a series of encounters with violent bands, adopts Pirrie’s survivalist tactics, killing in cold blood whoever gets in his way, dispatching the weak who, by his and Pirrie’s rationale, with die soon anyway.

The author plays a dangerous game by making John, essentially the book’s central character, increasingly unlikable. Essentially, The Death of Grass, like so many of the Christopher novels, is about how normal people are changed and forced to adapt when their everyday lives are pulled from under them. John’s wife Ann asks to shoot the last of the men who raped her and her daughter, not long after expressing horror over the shooting of three soldiers at a roadblock. No reassuring middle-class John Wyndham heroes here.

Different people are affected in different ways, and Sam Youd deals well with the psychological consequences on his characters of their harsh new surroundings. John Custance wouldn’t hesitate to sacrifice weak, ineffectual Matthew Cotter in the later novel A Wrinkle in the Skin (1965), for instance.

A massive earthquake has struck Cotter’s home of Guernsey, the extent of which he is soon to discover. In the first of many memorable jolts to the imagination, Cotter looks out to where the sea was and sees this:

It was like a glimpse of another planet, a strange savage and barren world. He could see the tangled green of the great weed beds, the rawness of exposed rock and sand … The blue sweep of wave was gone. A sunken land was drying in the early summer sun.

He soon falls in with a band of survivors and allows himself to be bullied by their leader, Joe Miller, but remains fixated on his daughter Jane, who was staying in Sussex when the disaster struck. Her chances of survival are practically zero, but Cotter refuses to believe it. He crosses the bed of the English Channel to look for her with a small boy called Billy, a disorientating experience as he feels the sea could come rushing back at any moment. Following a brush with an insane captain aboard a stranded tanker, they arrive at the mainland and soon meet another, more friendly group. Cotter is particularly taken by a woman named April, on the ruins of whose house they’ve made camp, and whose husband and children she reburied in the garden. April would seem to be the ‘love interest’ of the novel, but following an attack by marauding youths comes the second shock of the novel, when Matthew involuntarily reacts with disgust when she tells him she was raped by them, and has been several times before. She tells him:

‘I don’t fear you. But I despise you. I despise you as a man. As a person, I think I envy you… Nothing has changed for you, except the scenery. For the rest of us it was God bringing our world crashing down about our ears, but for you it was – what? An epic in Cinemascope, Stereosound and 3-D. Jane is still alive, and you amble your way towards her through the ruins. Do you know what? I think you’ll find her. And she’ll be dressed in white silk and orange-blossom, and it will be the morning of her wedding to a clean young man with wonderful manners, and you’ll be just in time to give her away.’

Even after this character assassination, Cotter continues on his quest with the boy, Billy. It’s Billy’s ensuing sickness, and the third major revelation of the book (in which we discover what happened to the sea), that finally snaps Cotter out of his fantasy. The book ends on a quiet note of optimism for the future.

The World in Winter (1962) opens by asking us to accept the outrageous premise that Earth’s been tilted a few degrees, plunging Britain into a new Ice Age and forcing people to flee to the now-temperate Africa and South America to become penniless refugees, consigned to live in shanty towns. It’s a clever idea, a reversal of fortunes that contains some serious comments on racism. The frozen London, plunged into the characteristic Christopher anarchy, is a lot more nightmarish than other attempts at the theme (John Boland’s White August (1955), for instance, is more silly than chilly), but the book lacks the raw power of The Death of Grass and A Wrinkle in the Skin.

I’m no great fan of Pendulum (1968), a overly reactionary novel that extrapolates social and political changes that were taking place in the late-60s. In a nutshell, the government abolishes student grants (an uncanny prediction, as it turns out), and in order to bolster their protests the students bring in yobs. Anarchy ensues. The end comes from an unexpected direction: religious zealots overcome the yobs by even more brutal means, and the book ends with a disturbing coda, showing Britain in the grip of these ‘Brothers’, punishing anyone who steps out of line with death or detention to the Scottish islands. The book was written in a climate of ‘youth versus society’, where student riots were rife; a few years before were the seaside clashes between the so-called ‘Wild Ones’, and the papers were full of sensationalised reports on ‘the Unattached’, the groups of young people who baffled officialdom by not being interested in Youth Clubs and the like. Public distrust of the young was strong, and Pendulum is just as guilty by assuming that motorcycle and scooter gangs would have their wicked way with the entire country, given half the chance. I can just about accept tilting the Earth off its axis, but the nature of this catastrophe is even more questionable.

The human race is despatched more ruthlessly in the young adult novel Empty World (1977). Here Sam Youd describes the origins of the novel, and perhaps many of the novels I’ve just discussed:

I recalled a boyish daydream, of thinking how much fun it might be if adults were somehow (painlessly, involving no guilt) to disappear, and leave the world to me and a few like-minded buddies. The joy, for instance, of finding an unattended, up-for-grabs Woolworth store… fortuitously laden with months of back issues of science fiction magazines… The book explored the darker side of the daydream

Fourteen-year-old Neil Miller’s parents have died in a car crash, leaving him to live with his grandparents near Rye (Sam Youd’s home, incidentally), but making him better equipped to cope with what follows: a plague that sweeps across the world, killing everyone around him one by one. It starts with the old, but soon the children find they’re not immune – the plague gives them a wrinkled, aged appearance before death, which makes the loss of two youngsters Neil comes across after he’s sure the virus has gone all the more shocking (‘He stopped some feet away, struggling not to show his incredulity and horror. A little old man stared at him from the face of a child.’). On his subsequent travels to London, Neil encounters only three other people, all children. He follows a message to a house, but finds the boy who wrote it was so consumed by loneliness that he hung himself only hours before. Later he finds a footprint in the Cosmetics department of Harrods and meets a pair of Girl Fridays, one of whom harbours a dangerous jealousy against Neil as he grows closer to her friend. The book is left open-ended, though not deliberately; a sequel was a possibility for a while.

The will to survive is strong in these books, but at the end of each it’s made clear that there are many more ordeals to come, and that humanity has to rebuild more than just its numbers.

The remainder of the John Christopher adult novels are a mix of different genres – thriller, psychological horror, some sf – but they often focus on an small group of people, isolated and fighting for survival.

In The Caves of Night (1958), a party of five people trapped in an Austrian cave system are gradually whittled down to the female lead, and her husband and her lover, and a situation in which she has to decide who lives and who dies. A Scent of White Poppies (1959) is a straight thriller about drug-smuggling (not one of Sam Youd’s favourites – his agent used to refer to it as ‘the dogshit book’ after an office typo rendered the title as ‘Puppies’!). The Long Voyage (1960) has an even more varied cast: dispirited sailors, a travelling circus family (and their bear!), an eloping couple with a typewriter case full of cash – all stranded in the Arctic after a storm cripples their ship. First Officer Mouritzen is a flawed hero typical of Sam Youd’s work: he spends the bulk of the book wooing Mary, who’s travelling with her daughter to marry a Dutchman she’s never met, but then, at a time of weakness, tries to bed circus girl Nadya. The Possessors (1965) concerns a party of tourists confined to a Swiss skiing chalet by an avalanche, under attack from an alien straight out of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Most significant are Cloud on Silver (1964) and The Little People (1967). The former reads an an intriguing cross between The Island of Doctor Moreau, Robinson Crusoe and Lord of the Flies. Again it concerns a stranded group of people, this time shipwrecked on a South Pacific island populated by deformed wildlife, and with a mysterious secret at the crest of the mountain that dominates it. Paranoia and mistrust grows, and there’s a science fiction solution, but it’s overshadowed by a climax that’s really very horrid indeed.

Equally disturbing is the ending of The Little People. Bridget Chaucey unexpectedly inherits a castle in the wilds of Ireland, and decides to run it as a hotel in the few months before her marriage to Daniel. She finds German artefacts everywhere, a barred room full of doll’s houses, and later a tiny footprint. Bridget and her new guests soon discover the Little People, initially believed to be of Irish legend, but found to be the results of wartime Nazi experiments in Germany. They appear harmless, but it transpires they can use some kind of mind control while the humans sleep to force them to confront unpleasant areas of their past (and future). Waring Selkirk, an American whose marriage has disintegrated into savage rowing, has a vision of himself and his wife a few decades in the future, their hatred more vicious than ever. Daniel proves to be a violent coward who runs away when his fiancée needs his help, and kicks one of the Little People with ‘not just anger, but the need to maim, to kill, to destroy utterly’. Stefan and Hanni Morwitz are hit the worst. He is a German who fought in the war; she is his Jewish wife, who the People feed experiences of a Nazi extermination camp. Stefan is consumed by guilt over his Nazi father (‘on terms of near equality’ with Himmler) and his desire for Hanni’s forgiveness for the atrocities of his people, leaving him in a kind of waking coma. The People themselves are merely catalysts to these events, which prove beneficial to some and devastating to others, and it’s to the author’s credit that he makes such a daft-sounding idea truly menacing.

As well as those under his own name, Sam Youd had also been writing novels under various other pseudonyms: humorous young-adult cricketing novels as William Godfrey; two novels about Felix, ‘the angriest of the Angry Young Men’, and an espionage thriller as Hilary Ford; four thrillers as Peter Graaf, three of them featuring Joe Dust, a private eye with a shady past over from Brooklyn; and a further thriller about Nazi spies as Peter Nichols. Then it was suggested that he should try to pick up a new audience by writing a science fiction novel for children. Futuristic novels no longer interested him (although, perhaps prompted by the excitement surrounding the Apollo missions, he would later write the bizarrely imaginative The Lotus Caves (1969)), so he took his inspiration from the past. The sf novel became a trilogy, and, apart from three Gothic romances written as by Hilary Ford (which he considered a poor attempt at emulating Jane Austen: ‘I have committed many follies, but never that of thinking I was in her league, or capable of promotion to its lower reaches’), he remained devoted to his new generation of readers.

After the Tripods came

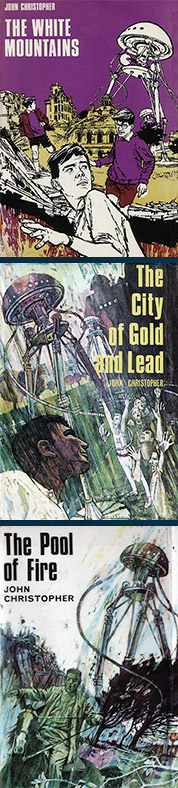

Returning briefly to The Twenty-Second Century, one of its short stories, ‘Weapon’ (1954), provides the clearest preview of things to come. The military use a boy who can see into the future to find out what the ultimate weapon will in a hundred years’ time – it turns out to be the crossbow. Sam Youd’s most famous novels are probably those set on a future Earth that has, for a variety of reasons, reverted back to a medieval, pastoral existence – the first of these works was the Tripods trilogy (1967/68). Generally regarded as the point at which children’s science fiction really grew up, the trilogy is detailed elsewhere in this issue, so I won’t dwell on it too long.

Returning briefly to The Twenty-Second Century, one of its short stories, ‘Weapon’ (1954), provides the clearest preview of things to come. The military use a boy who can see into the future to find out what the ultimate weapon will in a hundred years’ time – it turns out to be the crossbow. Sam Youd’s most famous novels are probably those set on a future Earth that has, for a variety of reasons, reverted back to a medieval, pastoral existence – the first of these works was the Tripods trilogy (1967/68). Generally regarded as the point at which children’s science fiction really grew up, the trilogy is detailed elsewhere in this issue, so I won’t dwell on it too long.

Part of the fun of the novels is their description of twentieth-century artefacts and places that are commonplace to us but mysterious and almost magical to Will and his friends. Early on in The White Mountains his father’s Watch, ‘a miniature clock with a dial less than an inch across and a circlet permitting it to be worn on the wrist’, is a source of wonderment to Will, as is this sign:

DANGER

6,600 VOLTS

We had no idea what Volts had been, but the notion of danger, however far away and long ago, was exciting. There was more lettering, but for the most part the rust had destroyed it. LECT CITY: we wondered if that were the city it had come from.

Will and Henry are introduced to maps by Ozymandias, and soon the country of the French, railway lines (the carriages are pulled by horses, but Beanpole envisages a more efficient form of traction powered by a machine ‘like a very big kettle’), and the City of the Ancients, Paris – again, not identified by name, but recognisable from the descriptions of the ruins. Here they find an underground ‘Shmand-Fair’, where, they later realise, Parisians must have made their last stand against the invading Tripods. There’s ‘a rack full of wooden things ending in iron cylinders’ – guns – and a box full of large metal eggs. ‘[Henry] picked one out, and showed it to Beanpole. It was made of iron, its surface grooved into squares, and there was a ring at one end. Henry pulled it, and it came away.’ Of course, there’s tension now for any reader who recognises the description as that of a hand grenade.

The rediscovery of our technology, most crucially balloons and bombs, eventually helps overcome the rule of the Masters, but the coda to The Pool of Fire, set two or three years later, shows that this might not be such a good thing. With the Masters’ suppression of mankind’s instinct to kill each other removed, we’re at each other’s throats again.

The later, modern-day ‘prequel’ to the trilogy, When the Tripods Came (1988), is more juvenile in tone, but nonetheless interesting. Common Christopher concerns resurface, such as families broken by divorce, and children’s resentments of a new step-family. It doesn’t really cast any fresh light on the earlier books, although there is some foreshadowing of events to come, and some nice digs at Brian Aldiss’s criticisms of a three-legged object’s basic inability to walk properly, and the Tripods’ lack of infra-red capabilities.

Following the Tripods trilogy, The Guardians (1970) again dealt with the value of freedom, and won Sam Youd, appropriately, both the Guardian award and the Christopher award for best children’s book, in 1971, and the prestigious German Jugendbuchpreis award in 1976. It tells of an oppressed future Britain in which great fences have been erected around the proletarian Conurbs (towns), where books and free thought are frowned upon. Any attempts to change the system are crushed using brutal means by the powerful Guardians, whose secrets the young hero Rob Randall discovers when circumstances following the suspicious death of his father force him to run away to the aristocratic County (country). A very powerful novel, originally planned, but never written, as an adult book; its themes are about as adult as a children’s book can get. Wild Jack (1974), originally written as an English-as-a-Foreign-Language text but later expanded into a children’s novel (though the latter was released first), is another fight for truth and freedom in a sterile, controlled Britain, with allusions to the legend of Robin Hood. The novel was originally the first of a trilogy – indeed, the follow-up was written but not released. Similarly written as an EFL text, Dom and Va (1972) is set half a million years ago, the grim tale of the conflict between a tribe of hunters and another, more culturally advanced tribe. A scene in which Dom tries to beat his female lover Va caused controversy with feminists, despite that fact that she thwarts the attempt – as a female colleague pointed out to Youd, Va is depicted as cleverer and more characterful than Dom, and gets all the best lines.

There’s a great deal of human ugliness in the Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1970-72) too. Again the setting’s a future England regressed to more primitive times, this time by volcanos and earthquakes, and an increase in solar radiation which has caused genetic mutations, known as ‘Polymufs’ and used as slaves. England is apparently under the power of the machine-hating Spirits and their human servants, the Seers. Luke Perry, Prince in Waiting to the city of Winchester, sees everyone he loves die around him, through treachery and deceit, during the course of the books, including his own brother at his own hand. He discovers the Spirits are faked by the Seers, who actually seek to reintroduce machinery and electricity, and see Luke as the ideal ruler for this aim. Luke falls in love with ‘Wilsh’ princess, Blodwen, and her father promises her to him, but her love is for his best friend Edmund. When he finds out, his stupid reaction gets him exiled from the city in disgrace. Luke’s wounded pride makes much of the final book uncomfortable reading. He gathers an army around himself, armed with lethal Sten guns made from specifications provided by the Seers, and fights for his honour and his title. Luke is determined that Edmund and Blodwen should die and Winchester should suffer, but blind to how wrong his actions are. Whole armies are slaughtered in the pages before the downbeat ending.

There are obvious allusions to the legend of King Arthur, from the sword Luke is presented with, to the play which triggers Luke’s suspicions of Blodwen’s true loyalties, based on the romance between Sir Tristram and Ysolde. A further short story, ‘Of Polymuf Stock’ (1971) is set during the events of the trilogy, and the most recent John Christopher novel, A Dusk of Demons (1993), returns to the theme of a controlling, but ultimately fake, religion created by those who seek to preserve, and eventually bring back, old-time technology, as the ending (reminiscent of John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids) reveals. It also has another post-catastrophe background, society having crumbled after being afflicted by a machine-fearing ‘Madness’. To anyone who writes this off as ‘kids’ stuff’, here’s the description of the eponymous Demons:

I saw a writhing tangle of shapes, winged and scaled and slimy, rotting faces oozing filth, hideous reptilian arms stretching out … reaching down to grasp me

Like The White Mountains, Fireball (1981) was conceived as a standalone novel, but the author returned to the story when another novel, a fantasy version of Arthurian legend, ground to a halt. The Fireball trilogy (1981-86) is an interesting alternate world story, which sees two cousins, the British Simon and the American Brad (again from broken families), transported by a strange fireball to a brutal Europe where the Romans still rule and slavery is common. Unwillingly swept along by the course of events, the boys realise that this ‘If’ world isn’t confined to Europe, and their adventures take them to the Americas and a China torn apart by civil war. Fireball, the first novel, starts off well, but most of the characters and bloody later events are told too swiftly to evoke much sympathy. The two central characters are interesting though, clashing personalities who often find themselves at loggerheads, and, by Dragon Dance, the best and most colourful of the trilogy, they’re even fighting for opposing armies. But during the trilogy’s three year time-span they realise they have more in common than they first thought.

The aforementioned A Dusk of Demons is Sam Youd’s last novel to date. As he describes in the following interview, he has attempted – and sadly failed – to interest a publisher in his memoirs. Also, since Dusk, a lifelong interest in Arthurian legend prompted him to try his hand at an adult trilogy told from the viewpoint of Marius Linus (aka Merlin); the first book would have culminated in a young Arthur seizing the sword from the Stone – but lack of time and the problem of finding a publisher in the difficult historical field intervened, and the project ground to a halt at Chapter 6 without even being given a title. Another novel, a futuristic adult ‘Eurothriller’ called Bad Dream, was completed a few years ago but not picked up by a publisher. I’ve been fortunate enough to read the first chapter, and can only say it would be a tragedy if the book isn’t published in one form or another (at the time of writing, there’s the possibility it might appear on the Internet at some point).

I hope that’s not the end of the story.

The adult novels are uncompromising, but Youd makes few concessions for children either. Not once does he talk down to the younger reader; his themes are every bit as sophisticated as before. At the heart of each of his books is solid storytelling and humane values, related by well-drawn characters we can all identify with, struggling in a world that’s falling apart around them. Whereas the running theme of the best adult John Christopher novels is ‘What happens to ordinary people when the props of civilisation are removed?’, in his children’s books the props are the other kind: the initially safe world of the lead characters is revealed to be a facade, usually stage-managed by evil or misguided oppressors. If this leads the young reader to be wary of institutions – whether they be governments, religions, or any other established edifice – to ask questions, then that’s just one achievement for which Sam Youd deserves the praise that opened this article.

Tags: books, john christopher, science fiction, tripods

-

Thanks for your appraisal of ‘John Christopher’. I thought he’d been forgotten by everyone except me.

I always cite ‘The Death of Grass’ as a favourite SF novel because it’s simple powerful central idea has stuck with me since I first read it in the ’60s. It’s the kind of SF I love to read and wish I could write.

I greatly enjoyed ‘Wrinkle in the Skin’ when that came out ; the sea-bed imagery has also burnt it’s way into my imagination.These two novels have been a yardstick that much other SF has failed to equal.Unfortunately when it came out I thought ‘The Little People’ was silly ; my love affair with the author ended and I’ve not read any of his fiction since.

Your article makes me think I should track more ‘John Christopher’ down.

Thanks again.

-

Wonderful to read his article again after so many years. I’ve done my best to track down Christopher’s works, but it seems I still have a ways to go. Fortunately, I have a copy of The Guardians and Wrinkle in Time to tide me over!

-

So pleased to stumble across your article…. I read Empty World at school and it started a strange love of post-apocalyptic storylines. I had no idea that Youd had published so many books, however. I’ll be filling my Amazon basket straight after I make this post.

Do you happen to know whether Empty World was on school reading lists in the 80s? It seems such a spooky choice for a schoolbook – but a great one.

-

John Christopher was the one person who turned me into a fan of Science Fiction after reading the Tripods trilogy on a whim when I was young.

One day several years ago I sent him a letter via publisher and was floored when he replied back with not only his standard form reply letter but also a hand written personal note telling how happy he was reading it.

What an amazing man.

4 comments

Comments feed for this article

Trackback link: http://www.colinbrockhurst.co.uk/the-shattered-worlds-of-john-christopher/422/trackback/